‘‘One reason the mouse worked and the others failed was, say you wanted to move the cursor from here to this dot - it didn’t have to be really accurate ,’’ Kelley says. While developing what became the Apple mouse in the ’80s, David Kelley was also working with trackballs and joysticks. (Top, a NASA control stick from 1956 bottom, a later Atari model.) NASA, David Corio for the New York Times

If you wanted the cursor to go up on the screen, you’d move the mouse forward, but they’d lift the mouse off the table, which was actually more intuitive, because it was closer to what they saw happening, and wanted to happen, on-screen.’’ Inevitably, this led to the allure, for kids and adults alike, of the touch screen.

But the mouse hit it right on.’’ Still, it wasn’t perfect. It moves to where it is that you need to stop, in other words. ‘‘Your brain and eye and hand are going to stop when you get to the dot. Decades later, similar mixed-use megastructures are popping up in Singapore, Shanghai and even Brooklyn. ‘‘It will be built somewhere,’’ Rudolph said. They wouldn’t have it, and the structure never got off the ground. The union-backed building, if successful, would undermine other unions (particularly plumbers and electricians). This turned out, however, to be a major mistake. He designed each unit to be built and nearly finished offsite, including pipes for plumbing and wires for electric. Rudolph had been fascinated by prefabricated housing and thought the mobile home could be the brick of his building. ‘‘We build an office building here and an apartment building over there.’’ A year earlier, the Amalgamated Lithographers of America union approached Rudolph to build a megastructure in Lower Manhattan, featuring two skyscrapers 65 stories tall, 2,100 parking spaces, plazas, an elementary school, restaurants, a marina and apartments, as shown in the composite to the left. ‘‘Look at what we are doing in our cities today,’’ the architect Paul Rudolph told The Daily Telegraph in 1968.

Franz reichelt timeline archive#

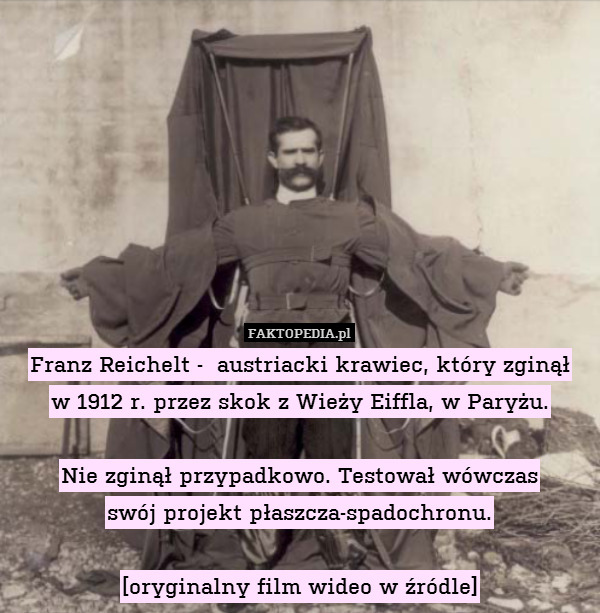

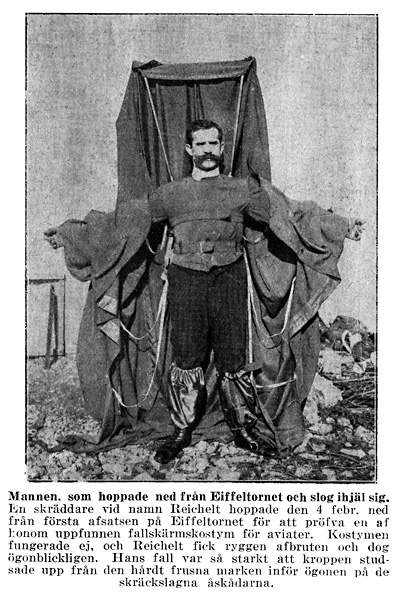

The Estate of André Steiner via Archive of Modern Conflict, Howard Levy Photo Collection/Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum via the Archive of Modern Conflict These days, about 20 people a year die in wing-suit crashes. But the wing suit returned with a vengeance - and better synthetic materials and air inlets - in 1999, when the world’s first commercial suit, also called the Bird Man, hit the market. He died on the wing too, in 1937, in front of a large crowd, when his chutes failed (shown here, a memorial). The wings were made of a kind of wool called zephyr cloth and a web of steel tubing, and he could glide several thousand feet after jumping from an airplane before opening his parachute and touching down, triumphantly, to applauding crowds. Decades later, Clem Sohn, above, and his homemade wing suit did much better. It didn’t, and though reports later claimed he died of a heart attack in midfall, he didn’t quite stick the landing. Known as the Flying Tailor, Reichelt wore folds of fabric hanging from his shoulder like drapery, stitched together to form wings and fill up with air upon flight.

4, 1912, in Paris, Franz Reichelt dove from the Eiffel Tower. The first fall came hard and fast, and it was fatal: On Feb.

Franz reichelt timeline generator#

Stirling’s idea would be confined to use as a backup generator (like the Philips model, shown here) for a century or so until Dean Kamen, who invented the Segway, brought the Stirling back as the basis of his Beacon generator, a 1,500-pound, washing-machine-size system that can be tied to solar panels or natural gas to power a small business, a rural village or, in his case, a very large eco-friendly home. But steam, which was an inefficient and dangerous power source when Stirling started, had improved and would provide the power and scale to drive the Industrial Revolution. Stirling and his brother, James, spent decades improving the engine before it was able to power a whole iron foundry in Dundee. In 1816, the same year that he became a minister in the Church of Scotland, Robert Stirling patented the Heat Economiser, which could take heat from anything - a fire, say, or the palm of your hand - and turn it into dynamic energy through the use of two pistons.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)